Disclaimer – Important

Heat training should be done in collaboration with an experienced coach or trainer and with prior medical clearance. Heat illness is a very real and dangerous thing, so work with a professional. If during any session you don’t feel good, just stop and cool down.

History and Background

There has been a lot of interest in heat training over recent years, which is partly fuelled by more events being carried out in high temperatures. For example, the Tour de France regularly sees high 30’s and low 40-degree temperatures. The other factors include the increase in understanding of the impact of heat on performance and the benefits of heat training in mitigating that decrease in performance.

Technology allowing the monitoring of core temperature has improved and become more accessible. The Core temperature sensor is the one most visible in pro sports at the moment. This has led to increased popularity amongst endurance athletes and their coaches. Which in turn has led in particular with the practical application of heat training within a training program.

Interestingly, while researching heat training I was really surprised to find the first recorded study into how humans adapt to heat was in 1768. So maybe we aren’t as cutting-edge as we thought!

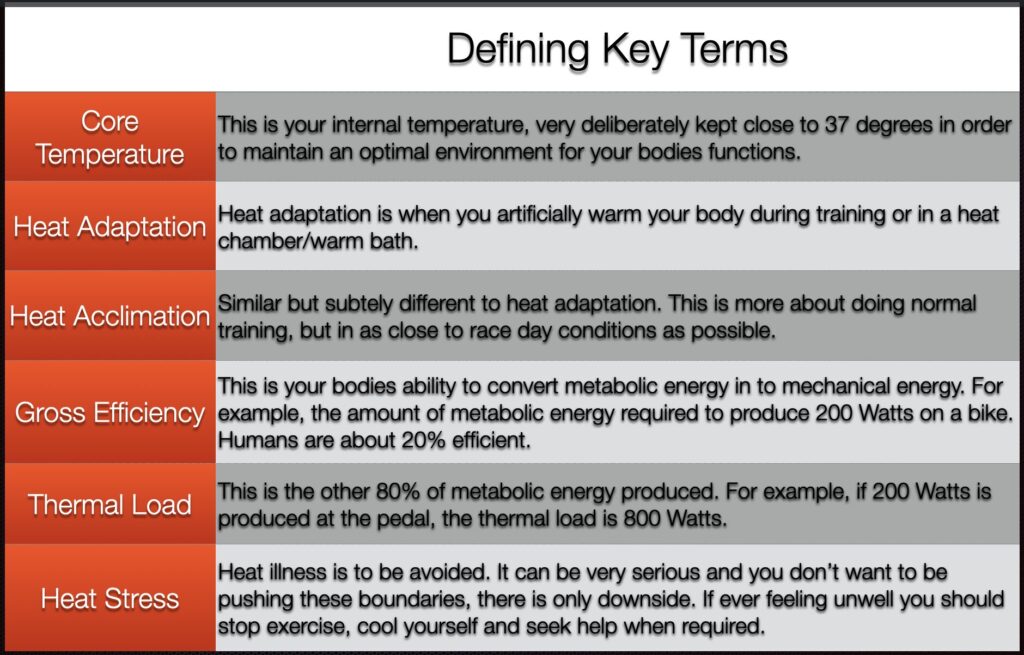

Before we get stuck in, he’s a quick reference to some key terms:

Why Heat Training?

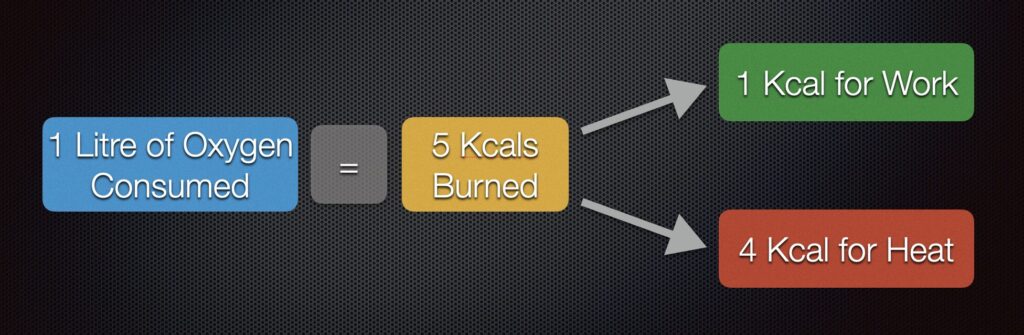

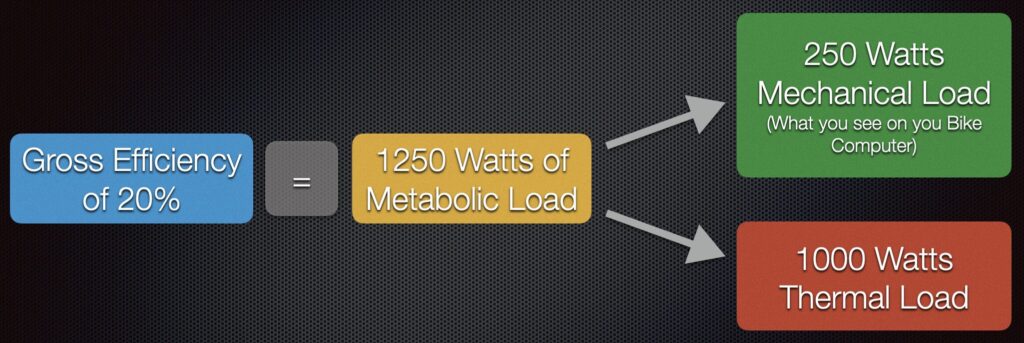

Maintaining optimal core temperature is extremely important to the body, and once exercising is a big task for your body. This is because the ‘Gross Efficiency’ of our body is around 20%. This means that 80% of the energy burned is converted to heat, which the body must deal with.

To make it a more practical example in cycling:

Your body has to deal with the thermal load in order to maintain the body in optimal condition. If that’s not possible, the workload has to be decreased. If it still isn’t possible, heat illness is a real risk and is extremely serious. That’s why you should be working with a professional and not just experimenting with this.

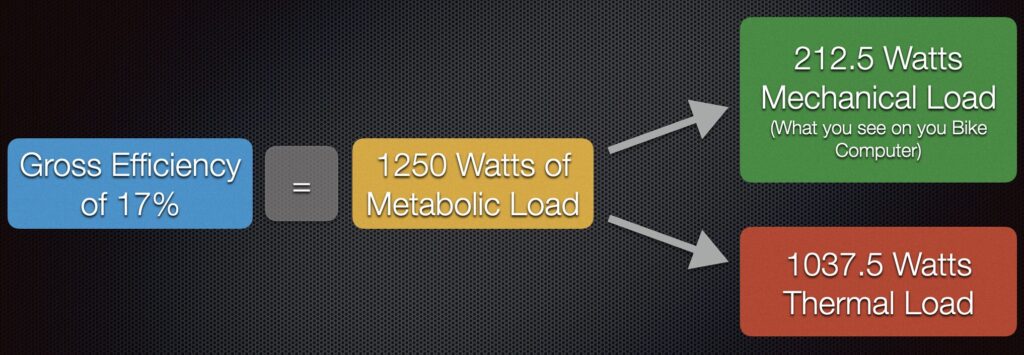

The current understanding is that Gross Efficiency decreases by about 1% for every increase of 1 degree in core temperature. Though this doesn’t sound like much, it’s actually quite a large effect. In the example above we assumed a gross efficiency of 20%. If this example was at a core temperature of 37 degrees, the diagram below shows the effect of a 3-degree increase in core temperature.

As you can see, for the same metabolic load, there is a loss of 37.5 watts when the core temperature is increased from 37 to 40 degrees. That’s certainly a significant change in performance. Increased core temperature will always eventually impact performance. The goal of heat adaptation is to mitigate some of the complex reactions that happen in the heat, allowing the body to maintain as close to peak performance as possible for as long as possible.

Our bodies are amazingly adaptable, and in moderate conditions, the mechanisms we have to dissipate the heat produced during exercise are extremely effective. The problems start to mount up quickly once the temperatures rise and dissipating the heat created by exercise becomes a big challenge.

The effects of heat on your body during a performance, like the adaptations themselves, are many. If you are not adequately prepared, your core temperature will rise more quickly, you will run out of the ability to sweat. The sweat you do have will be relatively loaded with electrolytes, that you will then run low on. As a result of increasing blood required elsewhere, processing nutrition will become increasingly hard and digestion will be impaired. All of which will result in your heart rate rising and your power dropping until the slowing down becomes stopping.

There are two main ways to continue to perform, one is to try and keep your core temperature down. If that is possible, ice, cold drinks, ice vests, etc can be used to keep the core temperature down. If successful the core temperature can stay in a range that allows for peak performance. If conditions are too hot/humid, this may not be possible. This brings in the other way to maintain performance in the heat. That is to train in a way that allows you to adapt to performing in the heat, and obviously, you can do both.

Heat Training – The Physiology

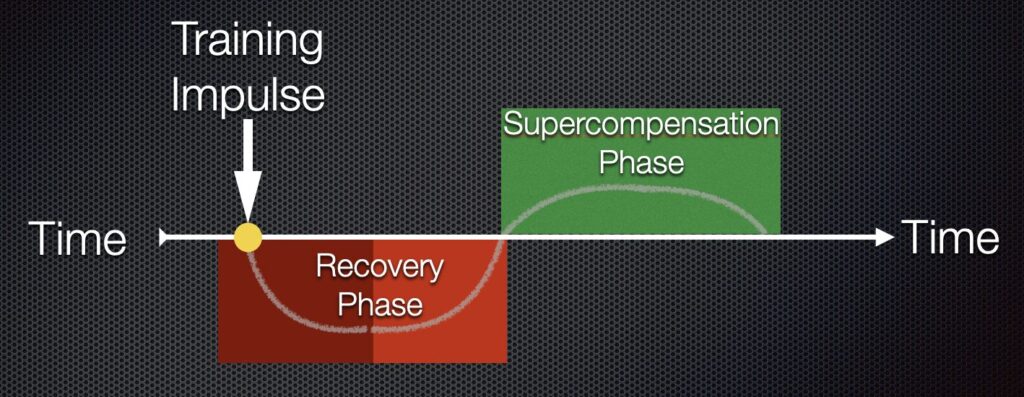

Training in any form is based on the idea that you challenge the body’s homeostasis (i.e. its optimal balance). By pushing the current limits you aim to trigger a reaction, where in time, the body adapts in preparation to better deal with the same stimulus in the future (as illustrated below).

The same is true of heat adaption. By exposing the body to training in the heat, the body will respond by adapting to perform better in the heat in the future. Though that sounds simple, the processes and mechanisms behind it are far more complicated. In fact, it isn’t a single response, the adaptations are numerous and it’s a combination that contributes to greater performance in the heat.

What are the Adaptations of Heat Training?

There are so many adaptations that occur when you are properly adapted to exercising in the heat. Interestingly, much of the research into heat adaptation is quite old and the adaptations have been well known for some time. For example, the increased sweat rate and decrease in electrolyte loss were well-established in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Other peripheral adaptations were found in the 1970’s, such as increased skin blood flow and earlier onset of sweating. A full summary and history of the adaptations can be found in the excellent paper by Periard, et al. 2015.

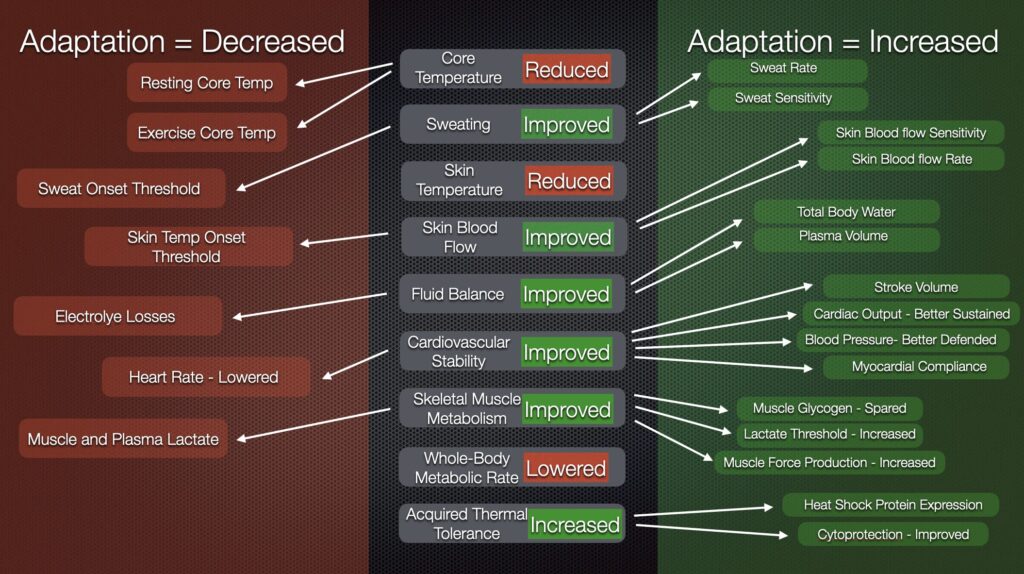

A summary of the adaptions is illustrated below:

In the diagram above, the 9 adaptations are highlighted in the center, with how the body achieves this adaptation to the left (if it decreases) or on the right (if it is increased). There is a big interaction between the different adaptations. For example, the increased blood plasma allows for an earlier and greater sweat rate without compromising hydration status as quickly. This increased plasma also allows for increased blood flow to the skin without having to compromise other body functions, such as digestion.

There is an increased sensitivity to the changes that occur when exercising in the heat. Meaning your body will start managing the heat more quickly, keeping you in an optimal range for performance for longer.

Non-Physiological Effects of Heat Training

All the mechanisms and adaptations above are physiological changes that occur with heat adaptation. A big adaptation that isn’t on this list is the psychology of heat adaptation. This is a huge benefit of heat training. From my own experience, when starting a heat training block, it was initially quite uncomfortable and the temptation to switch on the fans was very real, even during a short session. Whereas, later in the block I was comfortable at higher temperatures, at higher power outputs, and for double the time (my longest sessions were 90 minutes, with 60 minutes in the heat training zone).

This personal experience is backed up by many research studies. For example, in 2018, Malgoyre, et al. found that heat training not only increased performance in a 8km marching trial but also a significantly decreased rate of perceived exertion and thermal discomfort. These benefits should not be underestimated.

It is beyond the scope of this article to go into detail about all of these, as you can see, it’s an incredible amount of adaptation. For further reading, I would recommend the Periard paper in the references.

In Part 2 we will look at the protocols used for heat adaptation and how it can increase performance.

References

- Malgoyre A, Tardo-Dino PE, Koulmann N, Lepetit B, Jousseaume L, Charlot K. Uncoupling psychological from physiological markers of heat acclimatization in a military context. J Therm Biol. 2018 Oct; 77:145-156

- Periard, J.D., Racinais, S, and Sawka, M.N. (2015) Adaptations and Mechanisms of Human Heat Acclimation: Applications for Competitive Athletes and Sports. Scand. J. Sci. Sports. (Suppl. 1): 20-38.